What is the new collection of writer and volunteer Andrii Lyubka “War from the rear” about?

[ad_1]

In Ukrainian bookstores, you can finally find a new, long-awaited collection of Andriy Lyubka’s prose entitled “War from the Back”. A frank diary of a volunteer author or a fairy tale for Europeans? Or maybe all at once? Literary reviewer understood UP Culture, Arina Kravchenko.

There are texts about Ukrainians and for them. And there is – about, but not for. The difference is always felt, because in fact, between “for” and “not for” – there are light years of stories, experiences and meanings, so to be faced with the choice “for whom to write” is to choose a style, language and narratives that, leaving or not leaving the borders of Ukraine, aim to support something or undermine it, generalize or detail it, highlight it or leave it out of the frame. And it seems that Andriy Lyubka’s new book, “War from the Back” is a text where the author has not fully decided on the planet to which the book should go through hundreds of light years.

Andriy Lyubka – writer, poet, translator, essayist and volunteer. Those who follow the author’s social networks know that he very actively collects money for cars for the Armed Forces, buys them and delivers them to the front. The result of constant tireless volunteer activity was not only hundreds of closed needs of the military, but also a new collection of texts.

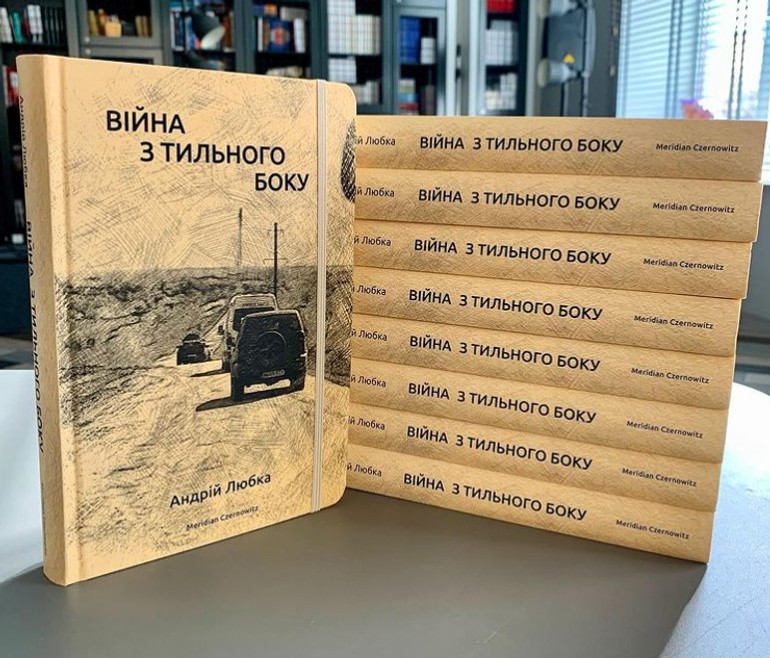

“War from the rear” is a collection of a wide variety of volunteer stories and experiences, collected under a rather unusual cover: rounded corners, small size, rubber that pinches the book – all this resembles a notebook, or rather, a moleskin.

This is a good design decision to at least partially explain the variety of texts that have gathered under the cover. So what? This is a kind of travel notebook: there are personal volunteer experiences, foreign cultural trawling, and private reflections on politics, society, and literature, and a verlibre for beatniks that praises the road, and retellings of stories told by military personnel, and several obituaries for fallen acquaintances. notepad Briefly about everything that worries and comes to mind.

This form is not new. Moreover, it seems that the format of short reportage sketches, overheard conversations, barely noticeable details is currently the most common way to write about war.

However, “War from the rear” is at the same time about something else, because on its pages, among others, we find, for example, the following: “I fervently support President Zelenskyi and appeal to all people of good will in Europe: recognize our right to become EU members in the future, send us a signal of support. Later – after the war – we will agree on terms and procedures, and now we need only one thing: that in in this terrible darkness, your lighthouse gave us a ray of light as a guide. Because the greatest deficit today is hope, which gives strength and courage. Give us hope, show us that we are not alone”.

Or this: “The desire for change was accumulating in society, as evidenced by the Orange Revolution and the Euromaidan. The war greatly accelerated the recovery process, and it turned out that the Security Service can protect the state and catch enemy agents, not just make business a nightmare. It turned out that representatives of the highest authorities and local self-government at the moment of truth can serve the state and the people, and not only take care of their own interests and those around them. And so on, and so in every sphere.”.

Andrii Lyubka’s collection was published by the Meridian Czernowitz publishing house

Meridian Czernowitz

The more often such passages, dated as far back as February-March 2022, come into view, the more certain it is that it is definitely not for internal use, because direct appeals to Europeans and lofty pictures of national reunification are present (and especially against the background of daily news accounts) cannot but cause an ironic smile.

However, at the same time, Andrii Lyubka cannot be accused of naivety. Vice versa. And this, in particular, is proved by a sharp and well-made essay, where the author writes about the meeting point of Ukrainians at the border, which works under the auspices of the UN, something like this:

“Since we are talking about working near a country where there is a war, the salary is here with all possible allowances and bonuses, so in a few months I will earn as much as I would have earned in Marseilles in two years. I hope that the war will last at least until the end spring, then I will manage to collect money for the repair of our summer house in the village. […] In short, everything is fine with me. Is it only Ukrainians who annoy me sometimes with different questions: if it weren’t for them, the job would be perfect in general”.

The glorification of the Ukrainian people, the constant emphasis on the genocidal character of the war (although not without an extremely unfortunate slide into a very unfavorable comparison of suffering like “this is terrorism, against the background of which even the Taliban seems to be a measure of morality and military dignity”), satirizing the international mission, explaining widely circulated memes and jokes – all this leaves a feeling that the target audience is not Ukrainians.

The feeling that all this is written for someone who is out of context to the point of not believing in the reality of Russian atrocities, supporting the “driving force” of the UN and the Red Cross and, of course, not knowing most of the most popular Ukrainian memes.

This feeling is also factually confirmed: the first presentation of the book will take place at one of the largest European book fairs in Leipzig.

Writing a text about Ukraine for a foreign audience is also not news. One of the loudest such practices was in particular “The Longest Journey” by Oksana Zabuzhko, written “by order” of a European publishing house with the aim of explaining to a non-Ukrainian reader what is happening in Ukraine. This example is indicative, as the publishing house and the author clearly communicated the purpose of writing, thanks to which the Ukrainian reader was neither “shocked” by the narratives that were obvious to him, nor was he indignant that the war was “explained” because of, say, an environmental issue. It was not for the Ukrainians, and therefore – in its own way, on the other hand, with the help of other tools.

Andriy Lyubka apparently had something similar in mind, at least this is the only thing that comes to mind when you read the following as of 2024: “There was no such unity at the time of the Maidans, because then we were divided politically, and another part watched indifferently. Nowadays, there are no indifferent people, even those who were forever spitting at their feet and waving their hands disdainfully have stood up, saying that nothing will change.”. Or this: “While the Russian soldier is waiting for an order from above, the Ukrainian soldier makes his own decisions, creatively uses the available means and weapons, improvises, twists, invents – and emerges victorious from the battle”.

Another thing that comes to mind is that “War from the rear” could have become a good fairy tale for Europeans, if it were not for the author’s attempt to balance between two worlds: internal – Ukrainian – and external. Because pathetic appeals to Europeans “don’t let Ukrainians choke” bordering on tragic, very private stories about fallen soldiers and extremely graphic sketches of harsh military life. The first one annoys Ukrainians, and the second one horrifies Europeans, unhardened by the daily consumption of such stories.

Thus, what both in form and content was planned as an honest and private conversation with the reader (since we are already looking into someone else’s notebook), in practice turned out to be a conversation with two strikingly different readers who need different things: someone – the bare, unfiltered truth , and some – tales about a beautiful, heroic people who seem to have stepped out of the pages of ancient Greek myths, the figurative system of which Lyubka turns to often enough to notice attempts to create a new Ukrainian myth. Although the “opposite” situation is, of course, also possible.

What does the assembly look like?

Meridian Czernowitz

This dichotomy did not allow the interesting and conceptually developed idea of the collection to be fully realized, but it did not prevent the formation of several important cultural and diplomatic messages that resonate equally with Ukrainian and foreign readers. This is the theme of an oriental attitude towards Central and Eastern Europe, and the birth of a generation whose biggest pre-war dream was not to flee to Britain, Germany or France to earn money (really?!), and the shame felt by wealthy and educated residents of Ukraine in Europe because of their own inconsistency with European stereotypes about refugees.

However, Lyubka’s strongest thesis, the thesis for which “War from the rear” was probably written, is this:

“Ukraine is often spoken of as a country between, between – between East and West, between Europe and Asia. It’s like we are a bridge. It’s a good metaphor, but in practice it’s terrible, because you don’t live on a bridge. It’s impossible to live on a bridge. The winds will whistle there , it is uncomfortable and cold there. There is a constant draft. A bridge is a structure for crossing. But not a home.”

Andrii Lyubka, “War from the rear”

It’s a really good metaphor that succinctly and aptly describes more than can be packed into a sentence or two. Following this metaphor, it is much easier to describe what “War from the rear” is. It is a bridge collection: half-diary, half-pamphlet, half-for-us, half-for-them, half-fresh and half-hopelessly-outdated. But in the end, is this a disadvantage? This is the most profitable way of communication so far. The one where it is easiest to converge on any of these “halfs” rather than on someone else’s side.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link