depression and despair in emigration in the works of the forgotten Ukrainian writer

[ad_1]

Olena Pchilka, Natalya Kobrynska, Ulyana Kravchenko, Natalya Romanovych-Tkachenko, Lyudmila Starytska-Chernyakhivska – these are just some of the names of female artists who, thanks to individual educational projects and publications, managed to be rediscovered recently.

The literary canon of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which, at first glance, could boast of the presence of only three cult female authors: Mark Vovchka, Lesi of Ukraine and Olga Kobylyanska – suddenly filled with new names, interesting texts, innovative approaches, unique topics and thousands of pages, which are worth both careful reading and careful understanding.

However, even such a positive movement does not mean that texts and personalities worthy of attention have been exhausted. Quite the opposite! Many of them are still waiting for their grateful reader and researcher.

In honor of the International Day of Struggle for Women’s Rights, a literary columnist UP Culture of Arina Kravchenko prepared material about Nadia Kybalchich: a woman with extraordinary talent and a difficult fate – she answered the question why she should finally be noticed.

To be born a writer in the third generation

Not everyone is lucky (and whether it is lucky is a question) to be born a writer in the third generation. Numerous repressions and wars actually left no traces of what could be called the words “lineage” or “dynasty”.

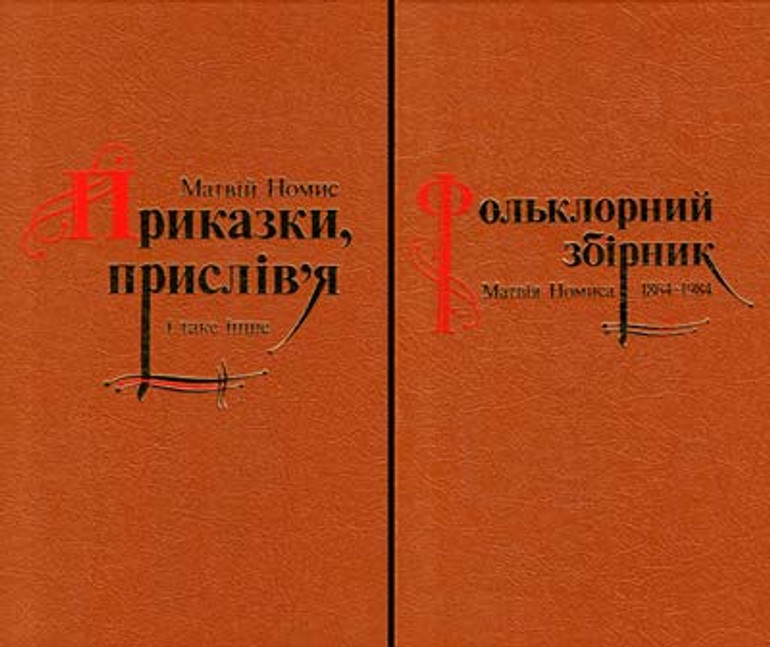

However, at the beginning of the 20th century, such families still existed and enriched Ukrainian culture with new generations of cultural figures. Nadia Kybalchich was born into such a family. Grandfather, Matvii Nomysworked in the first Ukrainian magazine “Basis”wrote stories, collected folklore and even compiled a collection of Ukrainian sayings and proverbs, printed in 1864.

Matvii Nomys, grandfather of Nadia Kybalchich

The mother, also Nadiya and also Kybalchich, is better known under a pseudonym Natalka Poltavkawas the author of short domestic stories, wrote dramas, some of which gained wide publicity both among professional and amateur theaters.

Contribution of Matrviy Nomis to the study of the Ukrainian language and culture

Thus, Nadiya Kybalchich’s daughter’s penchant for writing was organic and natural. Her environment, upbringing, her family’s connection to such iconic figures as Taras Shevchenkospirit of the times, further acquaintance and correspondence with Lesya Ukrainka and Ivan Franko – everything inspired me to write, to think, to live creatively. However, who knew that this very choice would also be life’s greatest challenge?

Natalka Poltavka (Nadia Kybalchich-Symonova), mother of Nadia Kybalchich, Jr.

The Young Child of Modernism: Impressionism and Revolution

Nadiya Kybalchich was only twenty when she first debuted in “Literary Herald” 1899.

One of her first short two-page sketches titled “Moonlight” tells the story of a young girl who, taking a short break from the bustle of the salon and leaving the guests, suddenly realizes how empty her life is. Pretentious meetings, beautiful clothes, cocky men, empty conversations – all this unexpectedly painfully affects the girl, who still has to go back, live on with the awareness of the incompleteness of her own existence.

Her other debut work is titled “In the forest” briefly outlines a day in the life of one family. The sketch is imbued with a sense of helplessness: the girl cannot talk frankly with her father, cannot leave sewing, cannot express her true thoughts and feelings, and even more so leave the house and go to the “broad will and the sun”. She is waiting for a book that is about to arrive in the mail and tell her more than the girl hopes to ever experience.

Portrait of Nadia Kybalchych

Already the first texts of Nadiya Kybalchich become an important, although currently unread, evidence of the life and psychological state of women at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Very soon, Nadiya Kybalchich attracted the attention of both Frank and Voronoi, was published in a wide variety of almanacs, magazines and anthologies, gradually becoming a full-fledged and active participant in the literary process of that time.

This is not surprising, because the young Nadia Kybalchich organically sensed the direction of those modernist creative searches that her older colleagues were concerned with. The texts of the early author, saturated with bright artistic details and captured second impressions, give every reason to talk about her as an impressionist, a supporter of the literary direction, the purpose of which was to record impressions, observations, and empathy.

The despair of emigration: being a “knight without fear and rebuke”

The demonstrations of 1905, which eventually led to the revolution, divided into “before” and “after” not only the history of the territory that existed under the name of the Russian Empire, but also the history of individual people who placed great hopes on all the explosive changes. Kybalchich was among such people.

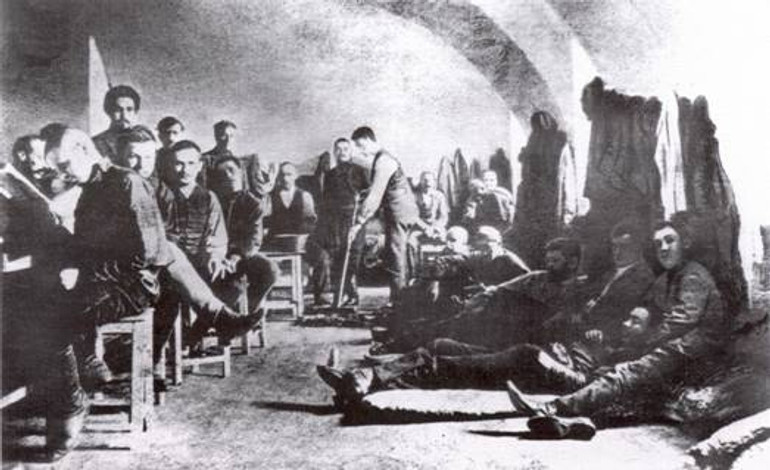

A rally during the October strike in Kharkiv. 1905

Observant and sensitive, she writes stormy civic lyrics during this period and sincerely hopes that “the truth will break out of the narrow dungeon.” Despite the fact that her poetry of this period radiates the typical pathos and optimism of the era, for Kybalchich herself it is a unique tone. After she and her husband survive the imprisonment of 1905 and go abroad for their own safety, not a trace of the inspired cheerfulness remains.

Only trouble and endless earnings awaited the couple in Italy, for which the author was desperate.

“It is impossible to imagine a cultured people without literature. In our country, writing is more important; it is a flag around which the faithful of their country gather; we expect more from it, and we want to see writers as “knights without fear and rebuke”. But in reality, they are not like that.”– this is how Nadiya Kybalchich thinks in “Letters” about the thankless, in fact unpaid work of a writer who has to bear the burden of superhuman symbolism both in life and in death, while not even having money for food.

A group of participants in the uprising in the Lukyaniv prison in Kyiv. 1905

Thus, we are dealing not only with a clearly expressed concern for the rights of the author, but also with the first proposals for the settlement of this problem. On this occasion, Nadiya Kybalchich writes the following: “It is time for us to have our own fund and help our writers in their hour of need. Remember what you have heard about their misery, throw away your carelessness and put this thought into practice. Our workers are living people“.

However, the author does not stop working on literary texts either: she translates a lot from Italian, is actively engaged in writing novels and short stories. Even then, inevitable changes begin to be felt in her prose.

To be or not to be – that is the question

“That person lived only to his own detriment/ And, like that star, disappeared somewhere without a trace“, Kybalchich writes in one of his poems.

The image of a person, or to be more precise, a woman who lives at her own risk, is the leading image in the author’s work during the period of emigration.

Poetry. Edition of 1913

More and more often, on the pages of her stories, we get to know characters for whom being is as scary as not being. Kybalchich’s heroes increasingly choose death over poverty, marriage with unlove, empty existence, toleration of injustice, love torments.

After returning from exile, Kybalchich settled in Kagarlyka, but soon the sick husband died, and the writer was left alone with unpaid bills and unpublished texts. On the eve of her suicide, the author publishes “Poetry” (1913), “Story” (1914) and “Children’s stories” (1914) at his own expense.

This same year, 1914, Nadia Kybalchich chooses not to be.

Epilogue: a woman author of the turn of the century

The Ukrainian literary canon, based on the examples of Mark Vovchka, Lesya Ukrainka, and Olga Kobylyanska, in particular, increased our faith in strong-willed women who had equal creative opportunities with their male colleagues. And although they often hid behind pseudonyms, they still spoke their own words loudly and confidently. However, such a modern vision should not be taken as evidence of a cloudless existence of a woman in the literary process of that time. Both the life path and the themes developed by Nadia Kybalchich testify to the difficult realities of the life of a female author at the turn of the century.

Social transformations that were still at odds with traditionalism and a certain rusticity, suspicion of female intellectuals, poverty, the inability to realize creative plans, forced emigration, and finally suicide, committed after the death of her husband, which meant complete loneliness and lack of protection in a still insensitive to the woman of the world – all this left no energy for full-fledged intellectual work.

And that’s why researchers of Nadia Kybalchich’s work agree that at the time of her death, the author was just beginning to fully reveal her true potential: if it weren’t for all these difficult circumstances, it’s quite possible that we would have a powerful and extraordinary novelist.

Children’s stories. Edition 1914

However, even under such conditions, Kybalchich turns out to be one of the few who developed the topic of depression, particularly female depression, so consistently and extensively. The characters of Nadiya Kybalchich’s sketches resemble butterflies in a trap: bright, helpless, inappropriate to the space they enter. All of them are about more, which, however, never comes.

It seems that the writer herself is more concerned: she is concerned about the same questions as her foreign colleagues, who are already cult, unlike Nadia herself: Charlotte Perkins Gilmanthe author of the classic story “Yellow wallpaper”and Kate Chopinwho wrote “The story of one hour”.

Rediscovering such authors as Nadia Kybalchich always makes you ask two questions. What heights would her talent have reached, if not for all the “ifs”, and don’t such rediscoveries prove that Ukrainian culture is not about “little literature”, but about great inattention to it?

[ad_2]

Original Source Link