What to read in April – a review of books from Chitomo

[ad_1]

The experience of others is that distant and unexplored world that we can touch with the help of books. Literature allows us to understand what other people around us are going through.

UP.Zhyttia recommends a new book review, made especially for us by a book expert from “Chitomo” – a novel about a home for the elderly, the most famous lesbian comic and the best translated books about war.

Olena Pshenychna. Where the sun sets

The topic of old age is still quite taboo in our literature. Elderly people in books often appear together with a rustic plot, which creates the impression that old age can only happen in the lap of nature and ethnography. Writers are more interested in old age as sources of folk wisdom. But we are all getting old, and you won’t be satisfied with one translated “Olivia Kitteridge”.

“Where the Sun Sets” is a novel about a Home for the Elderly. Vera is 72 years old, and she finds herself in it because her son volunteers in the war all the time, and her daughter-in-law was evacuated. Vera sincerely believes that she will not be here for long. It is uncomfortable for her to be here, but you get used to everything in this life.

The very space of a home for the elderly is full of situations of shame and embarrassment, situations that undermine the dignity of the elderly. Defecating in the potty at night and being under the constant supervision of a nurse in the shower is not something that is easy to put up with. Your body is no longer a private matter. These situations of deprivation of privacy and restriction of rights terrify the main character. But you can get used to anything.

Gradually, the book reveals the stories of people who ended up in a home for the elderly. They experience a lot of hidden emotions – the pain of the death of their children, the loss of the ability to do their work or live their usual life. They weave camouflage nets for the military and search for meaning in their new shared space. Some of them even think about new love (if, of course, as one of the heroines says, she happens to have a suitable grandfather).

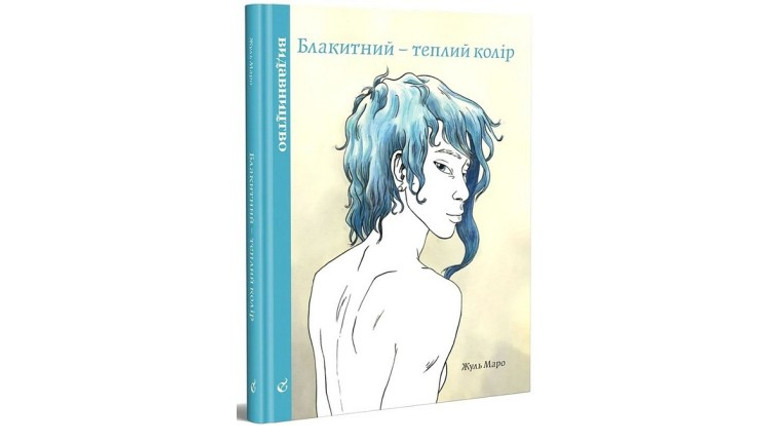

Jules Marot. Blue is a warm color

“Blue is a warm color” is probably the most famous lesbian comic in the world. Last but not least, thanks to his screen adaptation called “The Life of Adele”, which won the Palme d’Or in Cannes in 2013.

This is a story of teenage love, understanding one’s identity and finding one’s place in the world. The heroine of the comic is a schoolgirl named Clem, who feels disoriented and disconnected from the world. She does not understand why she does not feel joy from those actions that attract all her girlfriends – in particular, from the prospect of meeting a handsome high school boy.

But a bright ray of light appears in Clem’s life – a blue-haired girl named Emma, who is an open lesbian. Emma is a bit older and a lot looser. She does not hide her sexual orientation and is ready to defend it at pride parades, rallies and various art events.

For Emma, her sexual orientation is a political position that the girl is ready to defend. For Clem, her sexuality is an intimate secret. She painfully experiences her coming out both at home and at school.

The love story between the two girls in this comic is far from “and they lived happily ever after.” This is a story of constant misunderstandings, conflicts and problems that these two have to overcome while building their relationship.

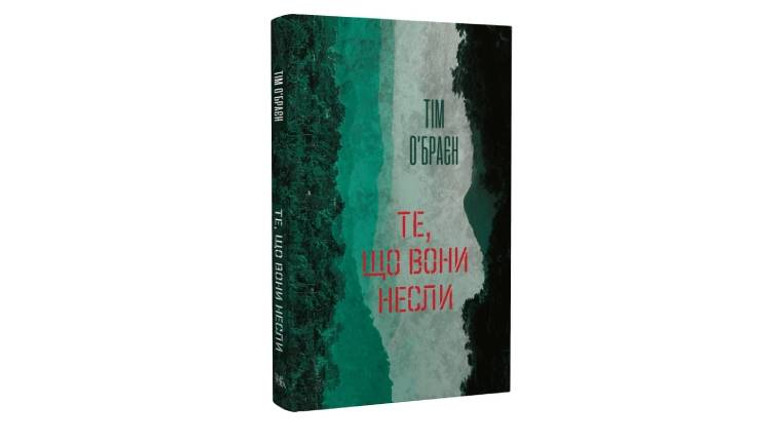

Tim O’Brien. What they carried

Despite Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulic’s claim that all wars are the same, this is far from the case. This is exactly the impression Ukrainian readers can get from the translation of the book by the American writer Tim O’Brien of the disparity of military experience. What They Carried is a collection of semi-autobiographical stories by a man who fought in the Vietnam War and is considered one of the best texts about the war.

O’Brien talks about participating in a war that was not his. The introductory text to this collection shows what soldiers actually carry with them in Vietnam. Along with material things, such as photos and letters from a beloved girl, there are also stories, feelings of derealization, friendship and a feeling of not understanding what they are doing here.

This constant wandering in the story is reminiscent of the tolling of souls or the medieval danse macabre, a well-known symbol of the futility and transience of life. These are people who move from village to village without gains, thrown here and doomed to move one millimeter to death.

In one of the texts, the author talks about his character’s complete resistance to the news of his own mobilization. The war in Vietnam had no value for him and he believed that only those who loudly approve of it should participate in the war. He was frightened by the thought of death. So much so that the hero seriously thought of escaping across the Canadian border.

These stories are full of strong emotions and bright life paradoxes. They show what sides the war can reveal, as in the story about the girl brought to Vietnam, who found in the war a wild thirst for her, for her adrenaline. They reveal the inner horror to which internal conflicts between themselves lead. This is a collection of masterful army stories that do not have a moral, but which are difficult to forget.

Susan Sontag. Observing the pain of others

In many modern novels, authors depicting war and violence ironically use the possibilities of the press and photography. All heroic and adventurous stories about the dissemination of incriminating footage and materials to the general public are rather romanticized. In reality, the footage of the war can affect the world, but it is not enough to change anything in the course of the war.

American writer and intellectual Susan Sontag’s essay “Observing the Pain of Others” is a continuation of the author’s thoughts about photography.

Far from all viewers, pictures of the war encourage the desire to do anything to stop it.

In this text, she writes about the role of the caption in war crimes photography and gives examples of how different sides of the conflict have repeatedly used the same photos as alleged evidence of the atrocities of their enemies. The narrative that some of the photos are staged is a phenomenon not only of the Ukrainian-Russian war. As Sontag writes, this phenomenon emerges constantly. Such words were heard even in the 1930s, when Guernica was destroyed.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link